Gallery Guide: "Potters on the Holston"

CURATOR’S FORWARD

The William King Museum of Art is proud to present Potters On The Holston, an exhibition that celebrates the long-lasting legacies of the stoneware potters of the 19th century and their impact on 20th century pottery in Washington County.

Thirty years ago, the Betsy K. White Cultural Heritage Project began documenting the decorative art and material culture of Southwestern Virginia and Northeastern Tennessee. Through the development and research of this project, the William King Museum of Art, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, and Washington County collaborated to specifically survey and document historic kiln sites to pinpoint the epicenters of pottery-making activity. During this time, research was conducted by many that The William King Museum of Art would like to continue to honor; including: Roddy Moore, Klell Napps, Marcus King, Skelly and Loy, Inc., Christopher Espenshade, the Ottery Group, and Charles Bartlett on behalf of the Wolf Hills Chapter of the Archeological Society of Virginia.

Without the dedication and hard work of this large collective, the exhibition may have not come to be. It is the love for regional history and the legacies of those that came before us by this proud Appalachian community that has truly made this effort realized. The research, education, and preservation of our regional history is a pillar on which our institution cheerfully stands and will continue to represent so that we may continue to honor the great leaders, artists, and contributions made by those who came before us.

Stoneware in 19th century Appalachia

While a great deal of archaeological information has been unearthed about the earthenware pottery traditions in our region of Appalachia, this exhibition focuses on the efforts of the stoneware artisans of the nineteenth century, influenced by the existence of the Holston River and its subsequent impact on local trade and industry. As the public became aware of the hazardous nature of lead glaze commonly found in earthenware, stoneware became more common. In the mid-nineteenth century the salt-glazed stoneware tradition migrated from New York and Pennsylvania to Virginia. Washington and Smyth County potters likely accessed salt from the mines in nearby Saltville for glazing pottery.7 Stoneware reaches a higher temperature than earthenware when fired and becomes vitrified, which means it will hold water. Betsy White, citing data recorded by Chris Espenshade, notes the increase of potters in the area as stoneware replaced earthenware:

“Through the second half of the century, stoneware pottery production and the number of potters increased significantly. At one point, Washington County, Virginia, supported more

Thomas Vestal was born in North Carolina in 1808.1 In 1850, Vestal’s Washington County, VA shop along the south fork of the Holston River near Osceola employed three workers, likely including John Wooten, and James Wooten. The 1850 schedule of manufacturers recorded Thomas Vestal investing $200 and spending $30 on 30 cords of firewood, producing crocks valued at $1000. Thomas was the father of Jessee Vestal and Simon Vestal, also potters in Washington County. Thomas’s daughter, Harriet D, married James Alexander Wooten in 1870, creating family ties among the Vestal and Wooten potters in the county.2

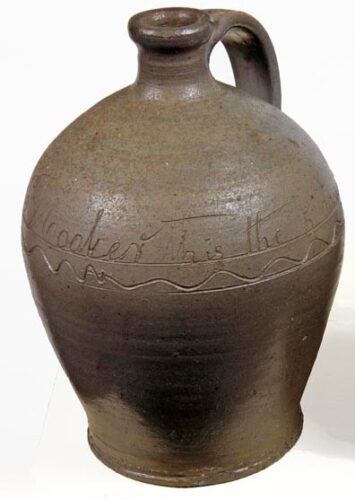

Jessee Vestal (born 1829) was the son, father, and brother of potters, indicating the importance of family in the pottery craft. His earliest known piece dates to 1849. This poem jug expresses the potter’s pride in his work. “Jessee Vestal, long and lazy, little and loud, fair and foolish, dark and proud, a splendee branda jug this is the 20th day of May 1849” Jessee Vestal may have worked at Miller & Sons in 1880.11 Jessee’s son, James T. also worked in Washington County. In 1880, he was 22 years old, living with Jessee12. James T. Vestal signed two known wares, a crock and a jug.

In 1860, Simon Vestal worked in the Forks district, living next door to J.L. Wooten and Robert Keys. Simon Vestal married Rebecca Ruth Harris, sister of the potter Alexander Harris.

WOOTEN

John Wooten was born in Iredell County, North Carolina in 1803.13 After 1828 when John’s son James L. Wooten was born in North Carolina, the family moved to Virginia.14 John T. Wooten was born in Virginia in 1840. John (senior) and James L. Wooten both likely worked with Thomas Vestal near Osceola in 1850. In 1860, James L. lived next door to Jacob Miller in Osceola, where they likely worked together until 1870.15

James L. Wooten was the father of numerous potters. Jehu (born 1849), James Alexander (born 1850 or 1851), Jehu (born 1852) and William T. (born 1865).16 Two signed pieces attest to Jehu’s availability. In 1870 James Alexander married Harriet D. Vestal, a daughter of Thomas Vestal. James lived next to potter Alexander Harris in 1870 and possibly worked with another potter John B Magee. James Alexander’s sons, William J. and Josephus J., also potted.17 In 1880 William J. lived next to C.W. Stockton and likely worked at the Osceola shop. William and Josephus continued working in the area until 1918.

William T. Wooten lived with his brother James Alexander in 1880, working in the family pottery. The 1860 census lists J. (John) T. Wooten living between Robert Keys and Simon Vestal, working as a potter. When a widowed John T. married Hettie (Hester) F. Foster in 1879, the register listed him as a potter.18 After 1880, the Wooten family continued potting in Osceola, but many moved to the Alum Wells area. In 1880 John T. worked in the Kinderhook district near Zenobia and Alum Wells, where Samuel Harris and Thomas Northcut likely worked for him. John T. Wooten’s sons Thomas C. (born 1870) and Charles (born 1872) continued working at the Wooten pottery shop.7 A close look at certain wares reveals small handprints, about 5” in length, suggesting the youths handled the work. Espenshade mentions the presence of youths in the shops: “There was a wide variety of tasks for unskilled or semi-skilled youths at a nineteenth century pottery, including digging of clay, processing of clay, making of balls, the application of handles, the preparation of kiln fuel, assistance in loading, unloading and firing of kilns” 8

In 1992, the Wolf Hills Chapter of the Archaeological Society of Virginia conducted excavations on Mendota Road at Wooten’s probable kiln site. The small, updraft kiln base was ten feet in diameter and constructed of brick. Characteristics from the excavation included: no albany slip on the interior, round coiled handles, and occasional beads beneath the rim.

MILLER

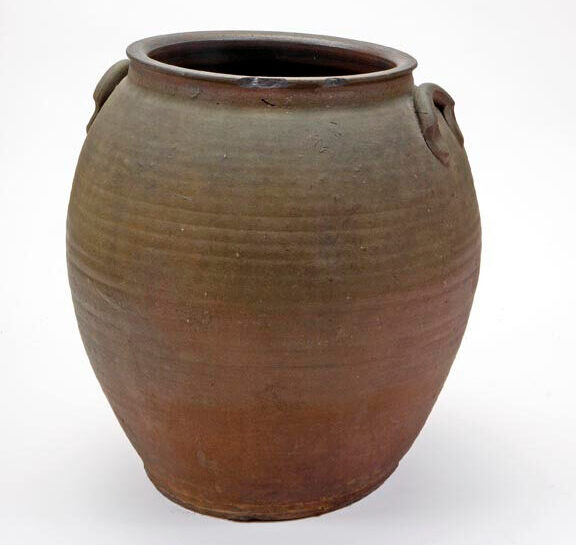

Jacob Miller, son of Adam Miller, owned a shop in the Forks District in Osceola in 1860.1 He employed three male laborers, likely James Miller, Robert Miller, and James L. Wooten, based on the proximity of residences. In 1870 Miller & sons operated 12 months out of the year, in contrast to the other county potters that operated seasonally. They produced over 14,400 gallons of stoneware, valued at $2,600. Between 1870 and 1880, the Millers moved their shop from Osceola to the south fork of the Holston River. By 1880, Miller & Sons produced pottery valued at $1000, and their shop remained idle four months out of the year.2 Four employees included Jacob’s three sons: James, Robert, and William Miller. The influx of new potters may have reduced demand for Miller & Son’s pottery between 1870 and 1880. The Miller & Sons shop continued through 1888.

One piece of stoneware has been attributed to James Miller by his grandson. Another crock has an “M” incised on the side wall. Sources indicate that James Miller signed his work with an “M”.

KEYS

Robert Keys, born in Washington County in 1824, owned a shop in the Forks District in Osceola in 1860, employing two male laborers, likely Simon Vestal and J.L. Wooten.23 The shop remained idle four months of the year. The manufacturer’s schedule records his shop producing $1600 in crocks and $400 in jugs.24 Keys was a successful farmer, a Justice of Washington County in 1856, and Deputy Sheriff in 1860. It remains unclear if he actually potted, or simply hired potters. By 1870, he had four helpers and produced 3600 gallons of stoneware, which sold for $600.25 An 1871 advertisement in the Bristol News referred to his pottery as the Osceola Stoneware Factory.26 C.W. Stockton and Robert Keys entered into partnership in 1879 and employed four workers in 1880. The Keys shop operated until 1888.27

The Wolf Hills Chapter of the Archeological Society of Virginia conducted salvage excavations at the Keys site in 1972. Characteristics included: heavy finger ridges on vessel interiors, single base beads, small, simple rims; gray and brown paste colors; limited cobalt underglaze decoration; jug handles at rim; albany slip on many interiors; and smoothed bases.

BIG SHOP STONEWARE

Washington County pottery experienced a surge in production after the Civil War. Potters trained in the stoneware tradition moved into Washington County, following the Great Road through the Valley of Virginia from the north. All identified wares from the postbellum era are stoneware, but the 1880 manufacturer’s schedule indicates earthenware continued to be made.28 Christopher Espenshade coined the term “Big Shop Stoneware” to define the shift from smaller family shops to larger operations with many workers. Vestal, Wooten, and Miller continued working in Washington County for three generations or more. Potters, primarily from the north, continued moving into Washington County, bringing cobalt decoration and stamps into the local industry for the first time.

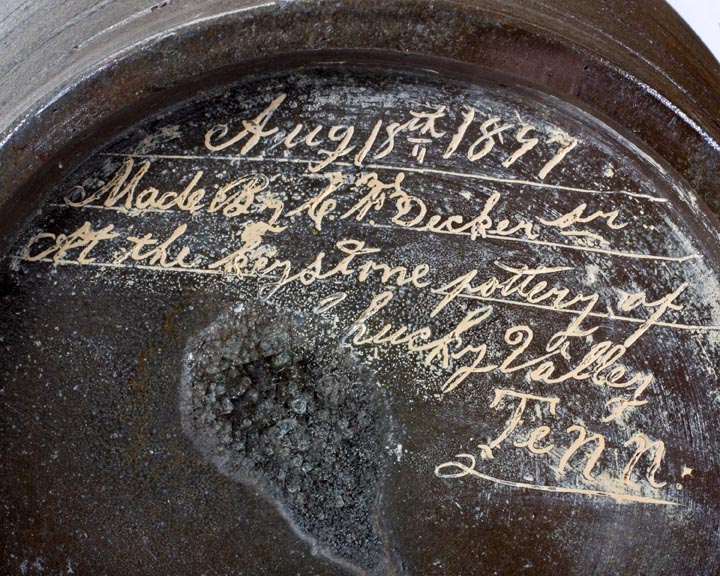

DECKER

Charles Decker, Sr. was born in 1832 in Baden, Germany, where both his father and grandfather worked as potters. He later worked at Remmey Pottery in Philadelphia after immigrating to the United States in the 1840s.29 Decker established the Keystone Pottery in Philadelphia in 1857 The birth of a second son places him in Delaware in 1859 and after 1869, he arrived in Abingdon. In 1870, Charles and his son, Charles F. Decker Jr, worked in the Mallicote-Decker shop.30 Augustus B. Mallicote owned the land in Rich Valley near Abingdon where Decker worked and may have provided financial backing for the pottery operation. The Decker family moved on to Washington County, Tennessee by 1871.31 Mallicote died in 1873.

John B. Magee and James H. Davis lived together near Decker and in 1870 likely worked at the Mallicote-Decker shop.32 Davis was born in Pennsylvania in 1844. He moved with Decker to Tennessee and continued to work at his shop, first as a potter and later running the store.

Archaeological excavations of the Mallicote-Decker site exposed an updraft kiln floor and numerous pottery shards. No intact pottery pieces are recorded from Decker’s Abingdon years. A survey of shards from the kiln site revealed the following traits: extruded lug handles; unglazed drain pipes; bright gray paste colors and well-developed salt glazes; clay tobacco pipes; and limited cobalt decoration in simple floral motifs.

MAGEE

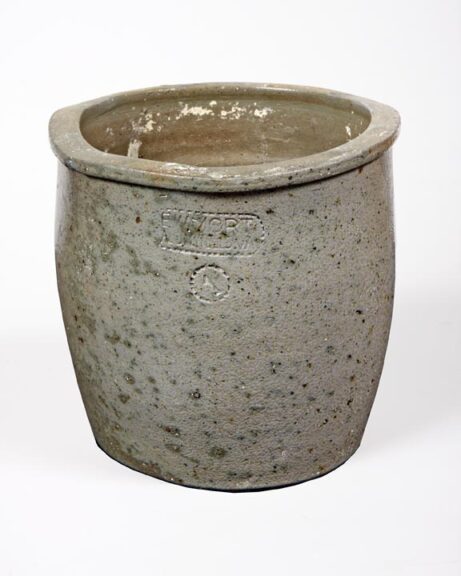

John B. Magee (Mcgee) was born in Canada in 1813 and lived in Cortlandville, New York in 1850.33 He operated a stoneware shop in Utica, New York in 1853.34 In the late 1850s, Magee moved to Cecil County, Maryland, where he operated a stoneware hop until 1867.35 By 1870 Magee had moved to Abingdon with James H. Davis and likely worked at the Decker shop. In 1873, Magee purchased land near Osceola, possibly the former Miller shop and in 1875 he bought land on the middle fork of the Holston River. The 1880 manufacturer’s schedule lists J.B. McGee as the owner of a stoneware and earthenware shop, producing $1900 in pottery. He employed four hands, including his son Fred Magee, J.M. Barlow, and Alexander Harris, based on the close proximity of residences. In 1880, the Magee pottery operated the full 12 months out of the year, in contrast to Miller & Sons and C.W. Stockton. In 1883 Magee sold the Osceola tract. At 17, perhaps Fred was unable to take over the shop.36

Excavations of the Magee kiln site revealed the following trends: unadorned bases; heavy and simple rims; Magee stamp highlighted in cobalt; cobalt decoration featuring a stylized flower with three petals, a thin stem, and two leaves- the left leaf higher than the right and painted before right; pulled jug handles; coiled lug handles (attached to the wall); and albany slip on interior walls.

BARLOW

J.M. Barlow was born in Virginia in 1856.37 An itinerant potter, he first worked in the Osceola area with J.B. Magee or Robert Keys and later in Alum Wells in the Mendota area. While living in Osceola, he used the stamp “J.M. Barlow, Ocola, VA”. Perhaps he moved to Alum Wells after Magee’s Osceola shop closed. He stamped these later pieces “J.M. Barlow Alum Wells”. He also used a stamp that simply stated his name: “J.M. Barlow”. Excavations at the Gardner shop near Alum Wells exposed three pieces with a Barlow stamp, suggesting Barlow also worked with Gardner.

The Wolf Hills Chapter of the Archeological Society of Virginia conducted excavations in 1973 at the Alum Wells site. The ten-feet diameter brick foundation suggested an updraft, bottle kiln. A stone, square platform surrounded the kiln base. The following patters emerged from the archaeological investigators: “Barlow Alum Wells” stamp (“S” backwards); “Barlow” rectangular stamp; rolled rims with subtle beads at the base; thin lug handles minimally compressed at their terminals; albany slip on some interiors; beads at the base of necks; and clay tobacco pipes.

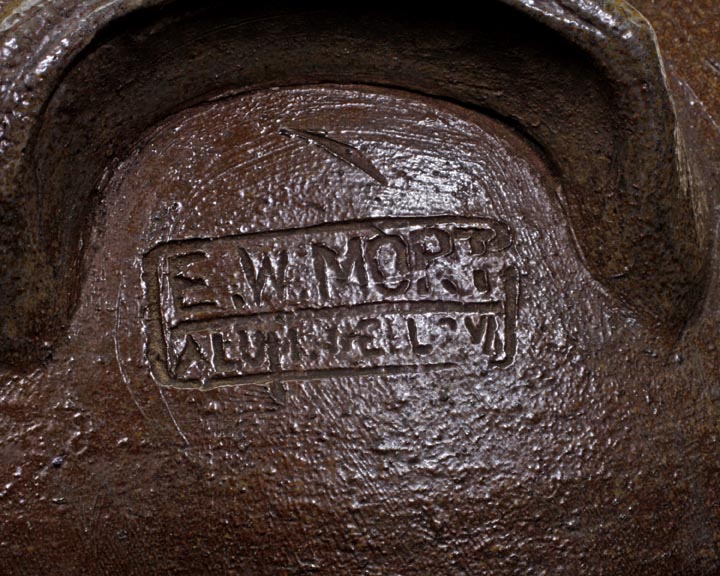

MORT

E.W. Mort (1853-1923) was born and possibly trained in Strasburg, VA.38 In 1880, he lived with Dr. Lancaster and worked as a potter, likely at the Stockton-keys shop or the Wooten family shop. An 1881 advertisement indicates Mort was in business at Alum Wells.39 Like Barlow, Mort also wrote his “S” backwards on “Alum Wells” stamps, suggesting they worked together. Archaeologists recovered a pottery shard stamped “Mort” from the Gardner excavation. A crock stamped ‘E.W. Mort Mohawk” suggests Mort worked briefly in Tennessee. In 1893, Mort gave up the pottery, married Amanda Cunningham, and became a Methodist minister. He died in 1923 and is buried in Emory, Virginia at the Holston Conference Cemetery.

GARDNER

John W. Gardner was born 1837 in Virginia and in 1850, he lived in Scott County, Virginia.40 In 1867, he purchased land in Washington County near Craigs Mill.

John W. Gardner, Jr. likely helped in the pottery shop at Craigs Mill, until the sale of the land around 1910. Archaeological excavations revealed the following traits: cobalt underglaze decoration; large coil-formed handles; unglazed drain pipes; “E.W. Mort Alum Wells, VA” circular stamp; and “J.M. Barlow stamp.”41

The Twentieth Century

The legacy left by the stoneware artisans continued to live through the direct impact of their incredibly populous industries and business ventures on the artisans who later potted in this region of Washington County, Smyth County, and the surrounding areas. Some of the most celebrated were Edwin and Mary Scheier.

EDWIN & MARY SCHEIER

The Scheiers crafted a legacy of sculpture throughout their entire lives together as husband and wife. Their history tells the story of fresh artistic endeavors as the couple formed their own American dream, shaping their nationwide success as easily as if it was on the potter’s wheel.

Ever the nomads, our Appalachian home is lucky enough to boast the site of the Scheier’s Hillcrock Pottery business, which began in 1938. While the couple only stayed in our region for a length of two years, it was just down Highway 81, in beautiful Glade Spring, Virginia that Ed & Mary catapulted their ascent into world-famous potters.

Benefitting from President Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Works Progress Administration, Ed & Mary began life traveling and teaching, making hand-made puppets and providing entertainment for school children. Through a series of “pure lucky breaks” as Ed later described in documentary Four Hands, One Heart, the two were offered the opportunity to hone their skills in clay and pottery as the overnight watchmen of a local kiln & studio. It was there that Ed & Mary started selling their wares and learning more about becoming fantastic business tycoons.

The early work of the Scheiers is characterized by “large and clunky” domestic wares with simple geometric motifs and soft glaze colors, often made of crushed glass. Their inspiration is a clear representation of Appalachian Folk Pottery in this region. Their Hillcrock Pottery business mainly introduced small figurines and functional wares, and during this time they began to learn the business market of pottery as well.

Throughout their travels and careers in teaching and the arts, the potters gained experience to develop their extraordinary skills, especially noted in their more mature works where the overall design, aesthetic, and craftsmanship expanded as their artistry did. These later prolific works were created in their resident studio in New Hampshire.

The extensive styles of the Scheiers are as varied as the forms of their works. Together, their collection of pottery ranged from decorative figurines to crocks & vessels; from plates & bowls to coffee pots & mugs. Their designs throughout the years evolved from early Appalachian Folk Art to the images inspired by tattoos Ed had seen while abroad during WWII, and continued on through their study of Zapotec pottery during their time in Mexico.